The study of Mediaeval buildings

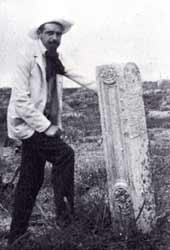

Giuseppe Gerola next to a tombstone in the Turkish cemetery at Herakleion. © De Luca |

The study of Mediaeval buildings on Crete began at the same time as Evans started to excavate at Knossos, because of the new opportunities offered to western scholars while the Great Powers ruled Crete (1900-1913). Giuseppe Gerola (1877-1938) worked on Crete from 1900 to 1902, appropriately enough under the auspices of the Venetian Institute of Sciences, Letters and Arts.

He made a huge photographic record of Venetian buildings on the island, and published his findings in four massive volumes; subsequently, Italian scholars have published more of his photographic archive (with drawings which unfortunately fall below Gerola's standards).

Venetian house at Anopoli: Gyro (recorded by Gerola) (1988). © Sphakia Survey |

Gerola's interests were broad, encompassing churches, fortifications, and domestic architecture. For example, he noted a Venetian-period house in Anopoli (Sphakia).

In later units we will look at the architecture of Khania (specifically in Unit 3 Session 3) and Patsianos (see Unit 4 Session 3) in the Venetian period.

Komitades Ag. Georgios: 3 bacini over the western door, 12th-early 13th centuries (1989). © Sphakia Survey |

Since Gerola, scholarly attention has rather focused on churches alone. Work has been done on the architecture of churches, especially those in major centres with some stylistic pretensions, but dating of modest churches (the majority of those built) has until recently been impossible. Only recently have scholars realised that valuable information can be obtained from the Italian or Spanish bowls (so-called bacini) often built into the walls of churches at the time of construction. For example, over the door of the church in Sphakia with fourteenth century paintings by Ioannis Pagomenos are three bacini of the twelfth to early thirteenth century.

Bacino from Crete: Italian Graffito Arcaica, perhaps from the Venice region. Gift of Mrs J. Hoare, granddaughter of Sir John Gough. Ashmolean Museum (inv. 1989-4). Courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford. |

They prove that the paintings do not date the church (as was once thought), and that they were added to a church already at least 100 years old.

A set of six bacini from Crete, which are now in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, illustrate the cultural processes at work in this period.

Bacino from Crete. Gift of Mrs J. Hoare, granddaughter of Sir John Gough. Ashmolean Museum (inv. 1989-8). Courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford. |

The bowls fall into two categories, Spanish and Italian, and date to the late fourteenth century. They come from a church in the environs of Herakleion. (They were presented in gratitude by the locals to a British District Commissioner, who had been appointed in 1898 to deal with the aftermath of a local massacre of Greeks.)

The placing of bowls in the walls of churches is a fashion borrowed from Italy, and must in some cases reflect the processes of religious imperialism. There were contemporary complaints about the numerous churches being built by Venetians on Crete. Some of the churches with bacini will have been built by Venetian landlords. Others (like our Sphakiote example) reflect the processes of cultural trickle-down, whereby locals imitate the practices of their rulers.