The Houses of Gortyn

The houses of Gortyn that have been excavated so far lie in the south-western sector of the site, ranging in date from Hellenistic to Late Roman in date, but thousands more await investigation in the fields that now surround the public buildings. At the edges of the inhabited area was a ring of cemeteries.

The urban form of Gortyn, as visible on the site plan, looks rather casual. Roman Gortyn did not have the grid plan known from other Roman towns, nor did it have the strict arrangement of architectural features we have seen in the Minoan palace at Knossos. Instead, Gortyn developed organically, like most Graeco-Roman towns: Gortyn was not restructured by the Romans when it became the capital of the new province: it simply received new Roman buildings and amenities.

The types of artefacts that this site has produced can be illustrated by analogy with objects in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Though they come from a variety of places in the eastern Mediterranean, they illustrate the range of objects circulating at Gortyn. We have divided them into four main functional groups (as we did for Knossos).

1. Table wares

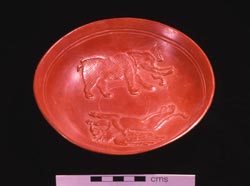

African Red Slip bowl. D. 0.172. Elephant and griffon decoration. Ashmolean Museum (inv. 1984.877). Courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford |

Table wares in the Roman period were often imported, first from Italy (Italian terra sigillata), and then from North Africa (African Red Slip) and western Turkey (Phocaean Red Slip). All of these were imported to Gortyn. We show here a fine decorated African Red Slip bowl.

2. Cooking wares

Amphoroid cooking pot, ?from Cyprus. Roman. H. 0.133. Ashmolean Museum (inv. 1960.757). Courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford |

Cooking wares often had a more local pattern of production and distribution (the mark-up was not enough to make long-distance sales financially sensible). However, in the Late Roman period, cooking wares too were traded over long distances, presumably carried with other, more obviously profitable products. Here we show a Roman cooking pot, probably from Cyprus.

3. Transport vessels

Rhodian amphora, from Tharros, Sardinia. Ashmolean Museum (inv. 1958.932a). Courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford |

Transport vessels (amphoras), unlike table or cooking wares, were traded not for themselves, but for their contents. Crete imported amphoras containing wine from the Aegean (and sometimes from further afield) from the Archaic through the Late Roman periods. We show here an amphora produced on Rhodes (of a type sometimes imported to Crete).

Rim and handle stump of pithos, from Dhiorios, Cyprus. Presented by Mr H. Catling. Ashmolean Museum (inv. D.M. 1958. A2, p. 11). Courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford |

Once amphoras had been emptied, they were often reused, either for further trade in wine, or as storage containers. In addition, specialised storage containers (pithoi) were produced. We show here part of a Roman pithos from Cyprus.

4. Specialised artefacts

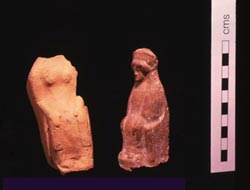

Two terracotta statuettes. (inv. 1910.389 on left, 1967.834 on right). Courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford |

Specialised artefacts fall into different categories. There are religious objects, whether marble cult or honorific statues, or more humble terracotta statuettes, mass-produced from moulds and sold at local sanctuaries. We show here two typical statuettes from the eastern Aegean, dating probably to the Hellenistic period. On right, you see a seated woman wearing a ritual headdress, from Rhodes? early first century BC; on the left, a woman(?) with hands resting on knees, from Cos.

Glass vessel. Ashmolean Museum (inv. 1949.176). Courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford |

There was a Demeter sanctuary at Gortyn, which was a typical location for the dedication of such statuettes. And there are luxury objects, like the glass vessels which become so common in the Roman period.

Finally, lamps, mass-produced from moulds, are common on Roman and Late Roman sites. They used olive oil for fuel.

Mould-made lamp, 5th century AD. Note the border of rosettes, and on the disc is a dove. Ashmolean Museum (inv. 1966.289). Courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford |