Biography of Arthur Evans

Arthur Evans (1851-1941) was born into a well-to-do family; his father was an eminent archaeologist and collector. After taking a degree in Modern History at Oxford, Evans travelled widely in northern and eastern Europe. In 1877, Evans became Balkan correspondent for the Manchester Guardian. When he married Margaret Freeman, the following year he and his wife set up house in Ragusa (modern Dubrovnik) on the Dalmatian coast.

In 1883 Evans and his wife went to Greece, where they met Schliemann and heard about his work at Mycenae and other Mycenaean sites. When Evans became Keeper of the Ashmolean Museum (Oxford) in 1884, he announced that his goals were to broaden archaeology beyond the classical period, and to collect and display a wider variety of ancient material.

Federico Halbherr on a horse (1984). © De Luca |

In 1892 Evans visited Rome, where he met Federico Halbherr, who had been working on ancient inscriptions in Crete (see Unit 3 Session 2 for further detail).

Evans' wife died prematurely in 1893 and it was not until 1894 that Evans made his first momentous visit to Crete. He had become interested in Aegean writing systems, through collecting engraved gems and seals for the Ashmolean. Evans visited the site of Knossos, and proposed to the local Cretan Archaeological Council that he would buy the land and excavate the site himself.

Drawing by the American diplomat William Stillman of part of Kalokairinos’ excavation, with a drawing of the Labyrinth on a later coin of Knossos (1881). |

Knossos was already known to be a rich source of archaeological information. Pococke had seen the (scanty) standing remains (see Unit 2 Session 1 Lesson 2), and in 1878 Minos Kalokairinos, from the nearby city of Herakleion, had dug trenches in what was later identified as the west wing of the palace (identifying the remains as those of the ancient Labyrinth).

Portrait of Sir Arthur Evans by Sir William Blake Richmond. Courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford. |

Schliemann too had wanted to dig at Knossos and had made some soundings there in the 1880s. He had obtained an excavation permit from the Turkish authorities in Crete, but had not been able to make a suitable financial arrangement with the landowner.

In Evans' case it was the political situation on Crete that prevented the start of his own work at Knossos. The Cretans were still waging their own War of Independence against the Ottoman Turks. The Turks left the island in 1898 and new Cretan government was established (see also Unit 1 Session 3 Lesson 4 for the history; Unit 2 Session 3 Lesson 3 for further information on a massacre outside Herakleion in 1898). But by early 1900, Evans had acquired both the Knossos site and an excavation permit, and work began on 23 March.

Photo of Iosiph Hadjidakis on a horse (1984). © De Luca |

Iosiph Hadjidakis began excavating Minoan villas at Tylissos near Herakleion, while Stylianos Xanthoudides excavated Minoan tombs at Koumasa in the Mesara plain to the south.

The Italians under Halbherr and Pernier began work at the Minoan palace of Phaistos and the villa at Hagia Triadha. Americans Harriet Boyd, Edith Hall and Richard Seager dug in east Crete at sites such as Kavousi, Gournia and Pseira. The French worked at the Graeco-Roman site of Lato, and eventually started excavating the Minoan palace at Malia in 1915. Other British archaeologists, such as D. G. Hogarth, R. M. Dawkins, and R. C. Bosanquet, dug at sites in central and eastern Crete, such as the cave of Psychro, the Minoan peak sanctuary of Petsopha, Palaikastro, and Kato Zakro.

By the time Evans began work at Knossos, he had already realised from the finds that had come his way that the culture of prehistoric Crete was different from that of the Mycenaean mainland, so different as to be 'non-Hellenic' in his eyes. He had therefore coined the term 'Minoan' to describe early Cretan culture.

What Evans found at Knossos confirmed this view. The monumental structure, which he called the Palace of Minos, with its elegant architecture; the bright, exuberant wall-paintings and pottery; the 'engraved tablets' in what came to be called Linear B - all these were different from anything that had been seen before. Evans worked hard to complete the excavations (1900-1905), and to publish them, chiefly in the six volumes called The Palace of Minos at Knossos.

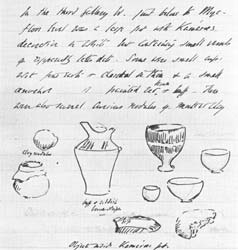

Page from Evans’ 1900 notebook showing drawings of some of the objects found beneath the floor of Magazine III (1983). |

Manolis Akoumianakis, Evans’ local foreman at Knossos. |

His local foreman, Manolis Akoumianakis, was an important part of the work.

Caricature of Sir Arthur Evans by Piet de Jong (1924). From R. Hood, Faces of Archaeology in Greece. |

R. Hood notes that ‘the background to this cartoon was occasioned by the finding of the House of the Frescoes in 1923 with its great stack of painted wall plaster … Piet somewhat wickedly has placed the raised forepaw [of the monkey] to echo the position of Evans’ own right hand.’ Evans was referred to by his right-hand man behind his back as ‘that monkey’.

It is easy to criticise Evans now, and indeed he was wrong about some important issues - he could never accept that the relationship between Minoan Crete and the Mycenaean mainland changed from Minoan cultural pre-eminence of the Aegean to Mycenaean administration of Crete including Knossos. He also made mistakes in some of the restorations he undertook at Knossos - but he made them not to aggrandise himself and his work, but to make the structures safe to excavate and visit. Evans remains the major figure in the prehistoric archaeology of Crete, for his vision and for his determination to bring the results of his work into the public arena.