Khania before the Venetians

(Click to enlarge) |

Venetian control of Khania is evidence in major monumental architecture. Some of this is still evident, because it was used subsequently by the Ottomans, some has been obscured through later buildings. The overall plan of the city, and the location of its major monuments is known through a whole series of Venetian drawings of the city. At least six different ones were published in the first half of the seventeenth century.

The lighthouse, Khania, (2002) . © Lucia Nixon |

This one, by Boschini, shows clearly the value of the enclosed harbour, with its lighthouse at the west end of the spit, and shows prominently the massive Venetian *fortifications (which had consumed the Roman theatre).

Venetian fortifications of Khania, (2002). © Lucia Nixon |

Kathy May photographing Sphakia Survey finds, in Khania, Venetian shipshed 4 © Sphakia Survey |

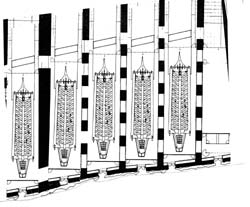

On the south side of the harbour are the 'Arsenali' or *shipsheds, which were built to shelter the galleys that formed the basis of Venetian naval power.

Plan of some of the Venetian shipsheds, with galleys. |

Venetian barrack block near the harbour, (2002). © Lucia Nixon |

On the western corner of the harbour was the *barrack block (visible in Boschini’s drawing), later built into the Ottoman fort (and now a Naval Museum).

Rector’s Palace, Khania, (2002). © Lucia Nixon |

On the Kastelli hill stood the Rector’s ‘Palazo’ or *palace, whose remains today are very scanty.

Agios Nikolaos, Khania. Aug 2002 © Lucia Nixon |

The religious life of Khania was also affected by Venice. Greek Orthodox *churches continued to serve the (majority) Greek population of the city.

Khania: Venetian monastery church of St Francis, now the main archaeological museum (2002). © Lucia Nixon |

The icons and paintings that decorated them we have already examined in Unit 2, Session 3 Lesson 1. But the Venetians, who belonged to the Western tradition of Christianity, needed new churches to serve their needs.

Interior of St Francis (picture by Gerola) © 'Vikelaia' Municipal Library, Herakleion. |

They built 23 churches in Khania, ranging from a large monastery church to small chapels. It was in the church of San Salvatore that the Englishman William Lithgow sought sanctuary in 1609 for having helped a slave escape from the Venetian galleys. It is now a museum of Byzantine art

Venetian church of San Salvatore, (2002). © Lucia Nixon |

The extent of such church building caused adverse contemporary comments from Cretans, though the practice of decorating the facades of churches with glazed bowls (bacini) became widespread on Crete, as we saw in Unit 2 Session 3 Lesson 2.

Etz Hayyim (or Zakynthiote) synagogue in Khania, (2002). © Lucia Nixon |

There was also a significant Jewish population in Khania, which lived just south of the main harbour. Their *synagogue was built in the late seventeenth century. Ruined during the Second World War (when almost all the Jews of Khania were killed), it has now been restored.