Art history: icons and wall-paintings

Our dominant image of the material culture of Mediaeval Crete (and Greece more generally) is that of religious images: icons and wall-paintings. At the start of this period, from 726 to 843 (with one gap), figurative images in churches were banned by the Byzantine emperors. This policy of so-called Iconoclasm was reversed in 843, and ever since then the Greek Orthodox church has endorsed the use of figurative images as a legitimate way of representing saints, Jesus, Mary, and God himself. Icons are images painted on wood. They can be mounted on screens separating the body of the church from the sanctuary, or displayed separately. The wall-paintings were done on the walls, normally of the naves, of churches.

Scholarship on this subject used to be purely aesthetic, and saw icons as images which needed simply to be dated relatively in order to be understood; absolute dating could be done on purely stylistic grounds. More recent scholarship has emphasised the fragility of dating on stylistic grounds, and has made progress by more extensive use of contemporary documentary evidence. It has also sought not to treat icons as autonomous objects, but as images to be read in relation to the social and religious worlds that created them.

Icon of Peter and Paul. Cretan, thought to be painted by Angelos, ca. 1450. Ashmolean Museum (inv. m.193). Courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford. |

The greatest period of production of Cretan religious images was in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. This period (part of the Venetian period) saw a cultural renaissance on Crete not just in art, but also in literature. There was a creative interplay in both words and pictures between Greek and Italian traditions. The choices to be made can be seen very clearly in the context of icons.

Angelos Akotantos, who came from Constantinople (Istanbul) and was active on Crete by 1436, represents the Greek pole. His work follows traditional Byzantine Greek models, with no trace of western influence.

Another great master of the same period was Nikolaos Tzafouris, active on Crete ca. 1500.

He was one of a group of artists of the second half of the fifteenth century, working in Herakleion, who followed the trends of Italian painting both in respect of technique and of iconography.

Icon: Pietà with SS Francis and Mary Magdalen, by Nikolaos Tzafouris, active on Crete, ca. 1500. Ashmolean Museum (inv. 1915.180). Courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford. |

Their closeness to Italian models meant that older scholarship attributed their work to Italian artists, but in fact (as is shown by documentary evidence) their style was a matter of personal choice and religious patronage.

Icon by Andreas Pavias of Crucifixion. © Benaki Museum |

Some of the icons of this period were commissioned for Italians, not Cretans, but this does not necessarily entail an 'Italian' style, and in some cases the same painter can be seen to be working in both styles in different parts of the same work of art. Italian partonage is illustraated by this Crucifixion by Andreas Pavias, second half of 15th century. Pavias was born and lived in Herakleion, but has signed his name in Latin script, showing that the icon was painted for an Italian patron.

Komitades Ag. Georgios: wall painting by Ioannis Pagomenos. © Sphakia Survey |

Wall-paintings in churches follow similar trends. In Sphakia there are fine examples from the fourteenth century of wall-paintings in local traditions. A major painter Ioannis Pagomenos, who worked in various parts of the island, was commissioned to paint a chapel at Komitades in Sphakia: the decoration included portraits of his two patrons.

Profitis Ilias 14th century wall paintings, looking NNE (2000). © Sphakia Survey |

Fine contemporary wall-paintings are also found in other Sphakiote churches.

One of the Cretan artists best known in the West today is Domenikos Theotokopoulos. He was born and trained on Crete, where he did his first paintings before 1567.

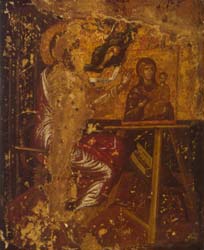

Painting by Domenikos Theotokopoulos (El Greco). St Luke. © Benaki Museum |

This icon was probably painted by Theotokopoulos for the Herakleion guild of painters, whose patron was St Luke. Its subject-matter is essentially Byzantine, but its style is wonderfully contrived: the main figure, St Luke, is very Italianate, while the icon of the Virgin Mary is thoroughly Cretan. In 1567 Theotokopoulos left Crete, first for Italy, and then to Spain, where he acquired the nickname El Greco. One of the works from his later period hangs today in Oxford (in New College chapel).