Palaces of the second period

The monumental complex which we call the Second Palace at Knossos reproduced many of the features associated with the First Palace. The most important of these is the combination of a rectangular Central Court oriented NNE-SSW, with clusters of rooms around it, arranged by function. In other words, rooms that in another architectural tradition might be grouped in separate buildings were instead kept together under one roof in a single complex.

We include the map of Crete below so that you may remind yourself of the location of the major prehistoric settlements.

MAP of Crete, Prehistoric phase © TALL |

(Click to enlarge) © A&C Black Norton |

There are other palaces of the Second period, notably those at Phaistos, Malia, and Kato Zakro; there might also have been one at Khania (we look further at this possibility in Session 3 Lesson 1 of this unit).

The basic description of the Second Palace at Knossos—groups of rooms around a Central Court—sounds very simple. The actual plan looks, and is, very complicated in terms of getting in and around and out of the palace, hence perhaps the concept of the labyrinth embedded in the myths discussed in Unit 2 (refer to Unit 2 Session 2 Lesson 2 for more information).

Though it is possible to distinguish room clusters architecturally, it is not always possible to determine their function, partly because of preservation, and partly because ancient structures, when excavated, do not come with helpful labels!

In this very short introduction, we will look at some of the main features of the neo-palatial Palace at Knossos, focusing on five areas:

- The western approach to the palace

- The West Wing (Knossos, not the White House!)

- Ceremonial rooms on and near the Central Court

- A palace workshop (NE)

- The residential quarter (SE).

Room numbers are those used on the plan on the screen.

1. The western approach to the palace

The Theatral Area, Knossos(2002). © Lucia Nixon |

An important route from the west led to the Theatral area (51), a stepped structure which may have been used to receive visitors.

The West Court, Knossos (2002). © Lucia Nixon |

A raised walk leads south to the West Court, built up to the west façade of the palace.

The rhyton-bearer, a fragment of a fresco from Knossos. Original in the Herakleion Museum. © Herakleion Museum |

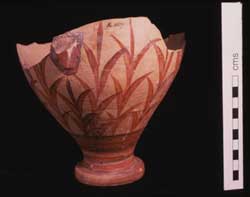

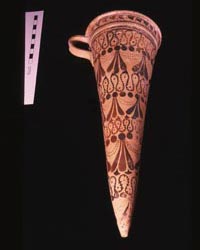

In the south-east corner of the West Court is the West Entrance and Porch (1) leading south to the Corridor of the Procession Frescoes (2). This fresco includes a figure holding a Minoan ritual vessel known as rhyton, described below in the section entitled Special Pottery.

South Propylaion and Horns of Consecration, Knossos. © Ministry of Culture Archaeological Receipts Fund |

The corridor runs south and then turns east, where one branch leads to the South Propylaea (3), a large gateway, connecting to the upper storey of the West Wing. Near the South Propylaea an emblem named by Evans ‘Horns of Consecration’ was set up.

The continuation of the corridor leads eventually to the Central Court.

2. The West Wing

Storage magazines, West Wing of Knossos © Ministry of Culture Archaeological Receipts Fund |

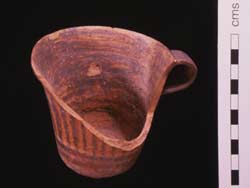

The ground floor consist of long narrow rooms running east-west, called magazines (23), used for tall ceramic storage vessels, or pithoi.

Large pithos from Knossos. Ashmolean Museum (inv. ae.1126). Courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford |

There is one example in the Ashmolean.

West façade of palace, with jogs (2002). © Lucia Nixon |

The west façade of the palace has two important features: first, the exterior wall is much thinker than the interior walls separating one wing from another. Second, the exterior wall, instead of running straight from north to south, is varied by a series of jogs.

Upper Floor, West Side, Knossos. © A&C Black Norton |

These façades with jogs are characteristic of many Minoan structures. The thickness of the wall meant that it could carry at least one other floor, and the jogs suggest where the main divisions for this upper floor might have been.

Evans called the upper storey the Piano Nobile, borrowing a phrase used to describe Italian palazzi. The large rooms here could have been the grand state reception halls.

3. Ceremonial rooms on and near the Central Court

Central Court, Knossos (2002). © Lucia Nixon |

The Central Court measures 50 x 25m.

The Throne Room, the Palace of Knossos . © Ministry of Culture Archaeological Receipts Fund |

A number of important rooms lie on or near its west side. An ante-chamber (13) leads to the Throne Room (14), here restored to its Third Palace phase.

Wooden copy of stone throne from Knossos, made to stand in the hall at Evans' house at Oxford. Courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford |

The original throne was made of stone called gypsum; this wooden replica, now in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, once graced Evans' house on Boars Hill nearby.

Faience figurine of Snake Goddess, from Knossos. Herakleion Museum. © Ekdotiki Athenon |

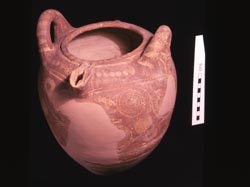

Opposite the throne was a small rectangular space below floor level, reached by steps. This space is called a lustral basin, because Evans thought it was the area for ritual cleansing.

Snake Goddess from Knossos. © Ministry of Culture Archaeological Receipts Fund |

To the south are the so-called Temple Repositories (19), where the faience figures known as the Snake Goddesses were found.

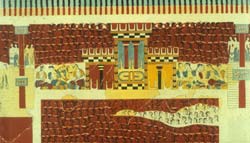

Knossos: Temple and Grand Stand fresco. |

The Tripartite Shrine (16) looks like the structure shown in the wall-painting known as the Temple and Grand Stand Fresco.

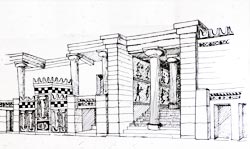

Knossos: reconstruction drawing of west side of central court (Tripartite Shrine). |

Pillar Crypt, Knossos (2002). © Lucia Nixon |

West of the Tripartite Shrine are two pillar crypts (20), small dark rooms thought to have ritual significance.

4. A palace workshop (NE)

Room (38) was a storeroom for stone specially imported from the Greek mainland - lapis lazuli Lacedaemonius, or Spartan basalt. It was used for stone vases. Room (39) was probably a workshop for the production of such vessels, and is known as the Lapidary's Workshop.

5. Residential Quarter (SE)

The residential quarter was set in the south-east part of the palace - a placement that reflects an eye for comfort in a hot climate. Rooms facing south or south-east get the morning sun all year round, and are cool by evening (crucial in the baking summers of Crete). There are other comfortable features here; the use of pier-and-door partitions. The piers are thick rectilinear pillars big enough for door panels to fold against. Light and air come from the south and east, and the amount can be varied by opening or closing doors, often built in rows of three or four. Indirect lighting is also provided by light wells, unroofed areas letting light into adjacent spaces.

The Queen’s Apartments, Knossos . © Ministry of Culture Archaeological Receipts Fund |

The final comfortable feature is plumbing, which includes a toilet which was flushed by a channel of water (30). Evans thought that women and men lived separately: he assigned a larger set of rooms to men, the Hall of the Double Axes (28), and a small set to women, the Queen's Megaron (29). There is no evidence for separate living quarters, but Evans' names for these rooms are still used.