Life in Neo-Palatial Knossos

Houses and urban form; pottery

(Click to enlarge) |

The Second Palace at Knossos was surrounded by houses of the same period, which varied in size and complexity.

(Click to enlarge) © Max Parrish |

The grandest houses reproduced a number of features seen in the palace itself. For example, the South House, located just below the south-west corner of the palace, was built partly of cut stone, and had at least two floors and a basement.

The house had rooms divided by pier-and-door partitions, a pillar crypt, lustral basin, and plumbing; one room had a wall-painting of a bird.

The plan of the house shows that several groups of valuable artefacts were recovered: a hoard of silver vessels inside the house, in the area of the pillar crypt, and an ivory griffin and lapis lazuli gem encased in gold from two findspots outside to the north. Though many governmental functions were probably carried on within the palace, valuable and prestigious objects did circulate beyond its limits.

Symbols and Motifs

Double axe, from side. Ashmolean Museum (inv. 1910.183).

Courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford |

Several objects and designs clearly had great symbolic meaning for the Minoans - even though we may not know exactly what their significance was. Double axes occur in two forms - solid functional axes, and axes made of thin, almost foil-like metal sheets, which could never have been used.

Double axe, from side. Ashmolean Museum (inv. 1971.849).

Courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford |

The word in Greek, labrys, is old and may be semantically linked to the word 'labyrinth' (house of the double-axe). In the South House there was a conical stand for a double axe, perhaps like the thin examples already mentioned.

Steatite vase fragment from Knossos. Ashmolean Museum (inv. ae.1247).

Courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford |

Horns of consecration have already been mentioned. This stone (steatite, also called soapstone) vase fragment shows a horn of consecration set on an altar-like structure outdoors, with a man walking (or dancing??) past it on the right, and a wall and tree in the background.

Faience figurine of Snake Goddess, from Knossos.

© Ekdotiki Athenon |

Snakes may also have had a particular meaning for the Minoans. This female figurine, made out of faience, holds a snake in each hand.

She is known as a snake goddess, but we have no way of determining whether she was a deity, a priestess, or a snake handler.

Rhyton in the form of a bull’s head, from Knossos. Height: 30.6 cm excluding horns. Herakleion Museum.

© Ministry of Culture Archaeological Receipts Fund |

Bulls occur with unusual frequency in Minoan art. This bull's head rhyton was found in the Little Palace, another grand house at Knossos.

It is made of serpentine with horns added separately.

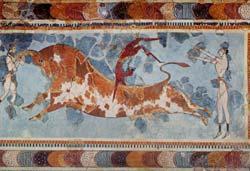

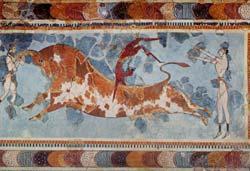

Bull-leaping fresco, from Knossos. Herakleion Museum (1984)

© Ekdotiki Athenon |

This fresco was found at the palace itself.

It shows two women (pale skin) and one man (dark skin) involved in bull-leaping where one person grasps the bull by the horns, a second vaults over the bull's back, and a third catches the vaulter.

Fresco from Knossos. Ashmolean Museum (inv. AE.1707).

Courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford |

Fragments in the Ashmolean Museum show a male leaper and a female leaper.

Fresco from Knossos. Ashmolean Museum (inv. AE.1708).

Courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford |

This ivory figure may also be a bull-leaper.

Ivory statuette of an acrobat, from Knossos. Herakleion Museum.

© Ministry of Culture Archaeological Receipts Fund |

The myth of the Minotaur may ultimately be linked to stories of Minoan bulls.

Marine Style vessel. Ashmolean Museum (inv. 1911.608).

Courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford |

And finally, marine motifs such as the octopus on this jar may also have had some religious significance, as vessels decorated in the Marine Style are usually found with other items of cult equipment.

The Queen's Apartments, Knossos.

© Ministry of Culture Archaeological Receipts Fund |

Compare again the dolphins in the Queen's Megaron.

Religious Places

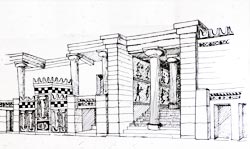

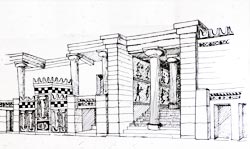

The Tripartite Shrine on the west side of the Central Court, Knossos.

|

The Tripartite Shrine on the west side of the Central Court was mentioned above.

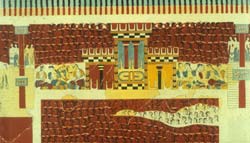

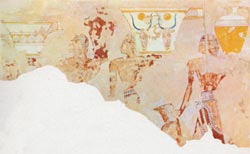

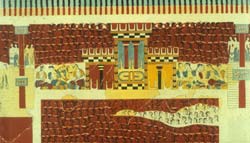

Knossos: Temple and Grand Stand fresco.

|

The Temple and Grand Stand Fresco is thought to depict this shrine.

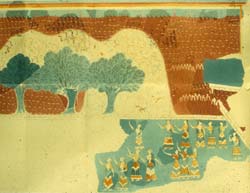

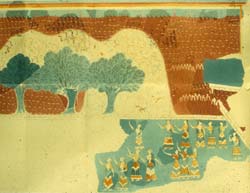

Fresco of Sacred Grove and Dance.

|

It has been suggested that the West Court may have been used for religious ceremonies. The Temple and Grandstand Fresco gives an idea of what these might have been like.

Libation table from Dictaean Cave, with Linear A inscription. Ashmolean Museum (inv. ae.1).

Courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford |

Outside the palace there were other kinds of cult places, such as peak sanctuaries set on relatively low hilltops with a good view of a major site and its territory. The peak sanctuary for Knossos is on Mount Juktas nearby.

View from inside the Dictaean Cave (1982).

© Sphakia Survey |

Another location used by the Minoans was caves. This stone libation table inscribed in Linear A (see below) was found in the Dictaean Cave in eastern Crete.

Entertainment

The Theatral Area, Knossos.

© Lucia Nixon |

The Theatral Area west of the palace could have been used for entertainment as well as for receiving important visitors.

Gaming board, from Knossos. Herakleion Museum.

© Ekdotiki Athenon |

And one suggestion for the location of bull-leaping at Knossos is the Central Court. But perhaps the best evidence for entertainment is this object identified as a gaming board.

Record-keeping

Libation table from Dictaean Cave, with Linear A inscription. Ashmolean Museum (inv. ae.1).

Courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford |

The stone libation table from the cult cave was inscribed in Linear A, a script whose language we do not know.

Two sealstones. Ashmolean Museum (inv. 1938.955 [blue], 1938.963[gold]).

Courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford |

Linear A was also used to write lists of people and commodities; the Linear B script used by the Mycenaeans in the Third Palace period to write Greek is an adaptation of Linear A.

Sealing. Ashmolean Museum (inv.1938.1153b).

Courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford |

The Minoans also kept track of commodities in transit by using stamp seals. Seals, and sometimes sealings - the impressions they left on clay used to close vessels and parcels - have been studied in order to understand this aspect of Minoan rule.

Foreign Contacts

Ivory statuette of an acrobat, from the Palace of Knossos.

© Ministry of Culture Archaeological Receipts Fund |

As has already been mentioned, Lapis Lacedaemonicus was imported from the Greek mainland. The ivory used to make the acrobat came from either Egypt or Syria.

Fresco of Blue Monkey from House of the Frescoes, Knossos.

|

Crete had many contacts in Egypt. Some Minoan frescoes depict monkeys, which were not native to the island.

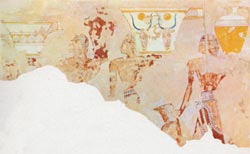

Wall-painting from the tomb of Senmut at Thebes in Egypt, ca. 1500 BC, showing Cretan emissaries bearing gifts (1967).

© Thames and Hudson |

This Egyptian painting from the tomb of Senmut at Thebes depicts people called Keftiu wearing Minoan kilts and carrying vessels of Minoan-type, included one decorated with two bull's heads.

Tell el-Dab’a: Water colour of fresco fragment with bull and male? youth. From remains of garden near Hyksos Palace, Egypt.

|

In the last ten years, fresco fragments have been found at Tell el-Dab'a in Egypt, in the remains of the garden near the Hyksos Palace, showing a young man in a Minoan kilt who may be bull-leaping.

Further Reading

Author(s): Jack L. Davis, Cynthia W. Shelmerdine.

Title: A Guide to the Palace of Nestor, Mycenaean Sites in its Environs and The Chora Museum.

Year: 2001

Publisher: American School of Classical Studies at Athens

Published in: Princeton

Author(s): Jack L. Davis (Ed.).

Title: Sandy Pylos: An Archaeological History from Nestor to Navarino

Year: 1998

Publisher: University of Texas Press

Published in: Austin

Author(s): Yannis Tzedakis, Holley Martlew.

Title: Minoans and Mycenaeans: Flavours of their Time

Year: 1999

Publisher: Kapon Editions

Published in: Athens

on Minoan food and drink etc.

Archaeology for Amateurs: The Mysteries of Crete:

© Alliance for Lifelong Learning 2002.

These pages are from a course designed for the Alliance for Lifelong Learning Web site, with an associated online discussion forum, and other functionality, and any references to these should be ignored.